Understanding PDA

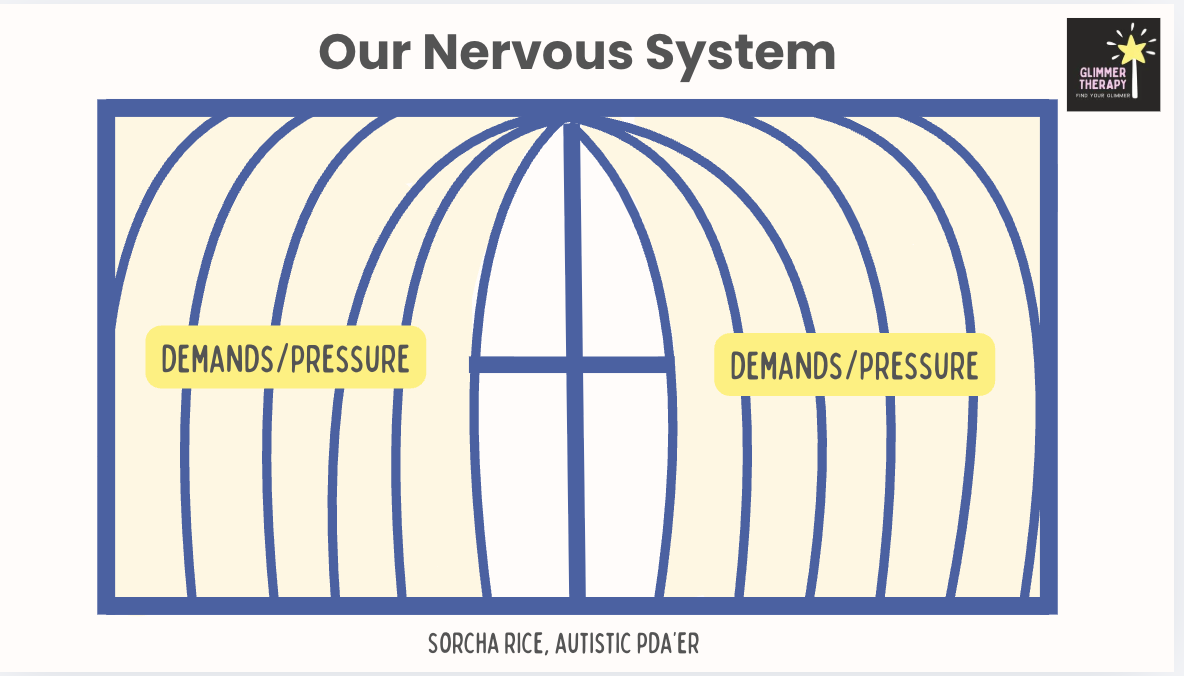

PDA is a nervous system response, not a behavioural profile

PDA is often misunderstood as oppositionality, anxiety-driven avoidance, or poor emotional regulation.

PDA is a nervous system response, not a behavioural profile

In reality, PDA reflects a heightened, threat-sensitive nervous system where demands and pressure (external, internal or self-imposed) survival responses (trigger fight, flight, freeze, or shutdown responses).

This is not a choice. It is not manipulation. It is not a lack of skills.

It is a survival response.

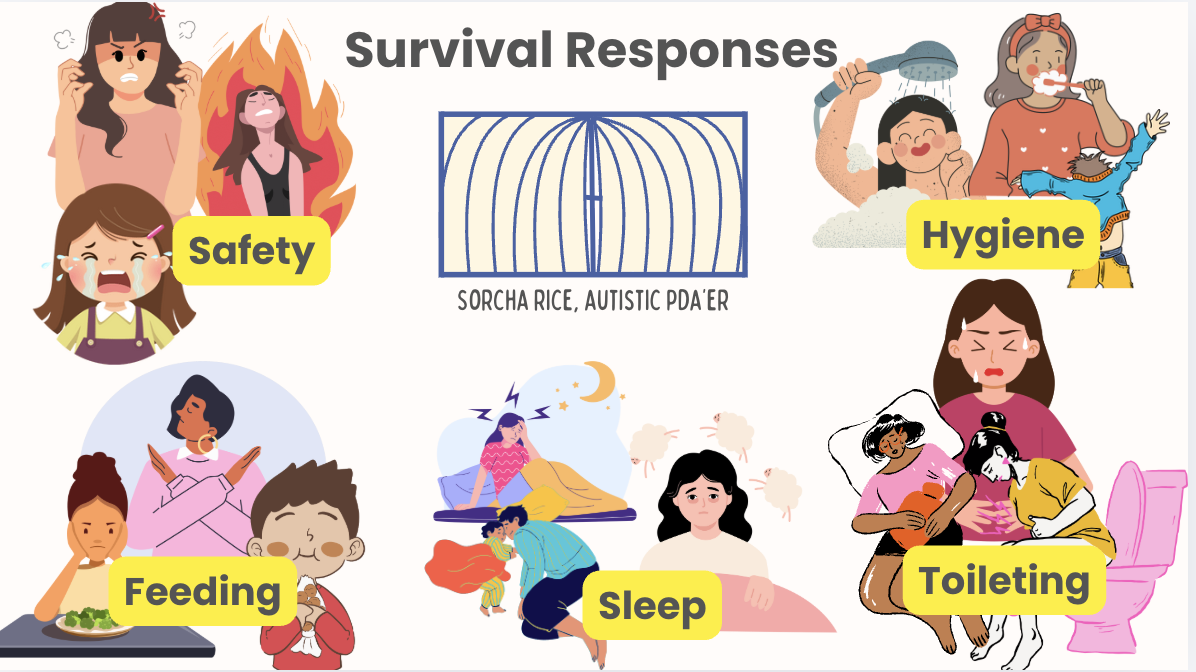

How PDA can show up

PDA does not only show up as saying “no” to demands.

Because PDA is a nervous system survival response, it often affects access to everyday activities when capacity is reduced. These changes are not deliberate, manipulative, or permanent losses of skill. They are signs that the nervous system is under threat and operating in survival mode.

Capacity fluctuates. When safety increases, access often returns.

Self-Care

When nervous system load is high, everyday self-care tasks can become inaccessible.

This may include:

difficulty with washing, dressing, brushing teeth, or hair care

decreased capacity for routines that were previously manageable

distress linked to sensory input, sequencing, or time pressure

These tasks require motor planning, interoception, sensory processing, and a sense of safety. When capacity is reduced, self-care is often one of the first areas affected.

Feeding

Feeding is highly sensitive to nervous system state.

When capacity is low, PDAers may:

rely on a very limited range of safe foods

eat significantly less or skip meals (especially at school)

experience nausea, gagging, or distress around food

meet criteria for ARFID

This is not oppositional behaviour or “being fussy.” Eating requires safety, regulation, and tolerance for sensory input. Loss of access to food variety or appetite is a common nervous system response to threat.

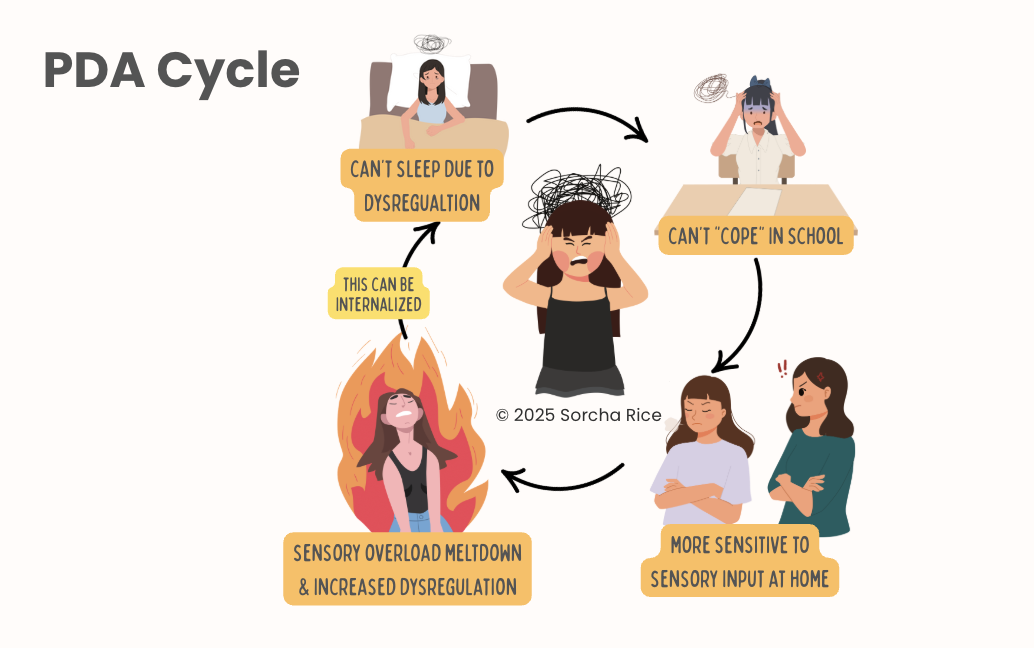

Sleep

Sleep is another area commonly affected when the nervous system is overwhelmed.

This may look like:

difficulty falling or staying asleep

needing to co-sleep for safety

sleeping during the day and being awake at night

frequent night waking or nightmares

Sleep changes are not behavioural choices. They reflect a nervous system that does not yet feel safe enough to fully rest.

Toileting

Toileting difficulties are a very common and often an early signal that capacity is closing.

This can include:

constipation or stool withholding

urinary urgency or accidents (overactive bladder)

recurrent UTIs

avoidance of toileting environments

Stress and threat directly affect gut motility, pelvic floor coordination, and interoceptive awareness. Toileting changes should always be understood through a nervous system and physiological lens, not as regression or refusal.

Safety

When capacity is significantly reduced, some PDAers may engage in behaviours linked to safety concerns.

This can include:

harm to self

harm to siblings

harm to parents or caregivers

risk-taking behaviours or bolting

These behaviours are survival responses, not intentional acts of harm. They often function to discharge overwhelming internal states, regain a sense of autonomy, or create distance from perceived threat.

Support must focus on restoring safety and reducing nervous system load, not on punishment or control.

Communication

Communication often fluctuates with nervous system state.

When capacity is reduced, PDAers may:

speak less or stop speaking altogether

rely more on gesture, behaviour, or non-verbal communication

use scripting, echolalia, or gestalts

struggle to access language even when previously fluent

This is not refusal or disengagement. Language access is state-dependent. As safety and regulation increase, communication often becomes more accessible again.

These changes are not separate problems to be treated in isolation.

They are interconnected signals that the nervous system is under strain.

When pressure is reduced, autonomy is honoured, and regulation is supported through relationship and environment, capacity can reopen and access to self-care, feeding, sleep, toileting, safety and communication can return.

A key point

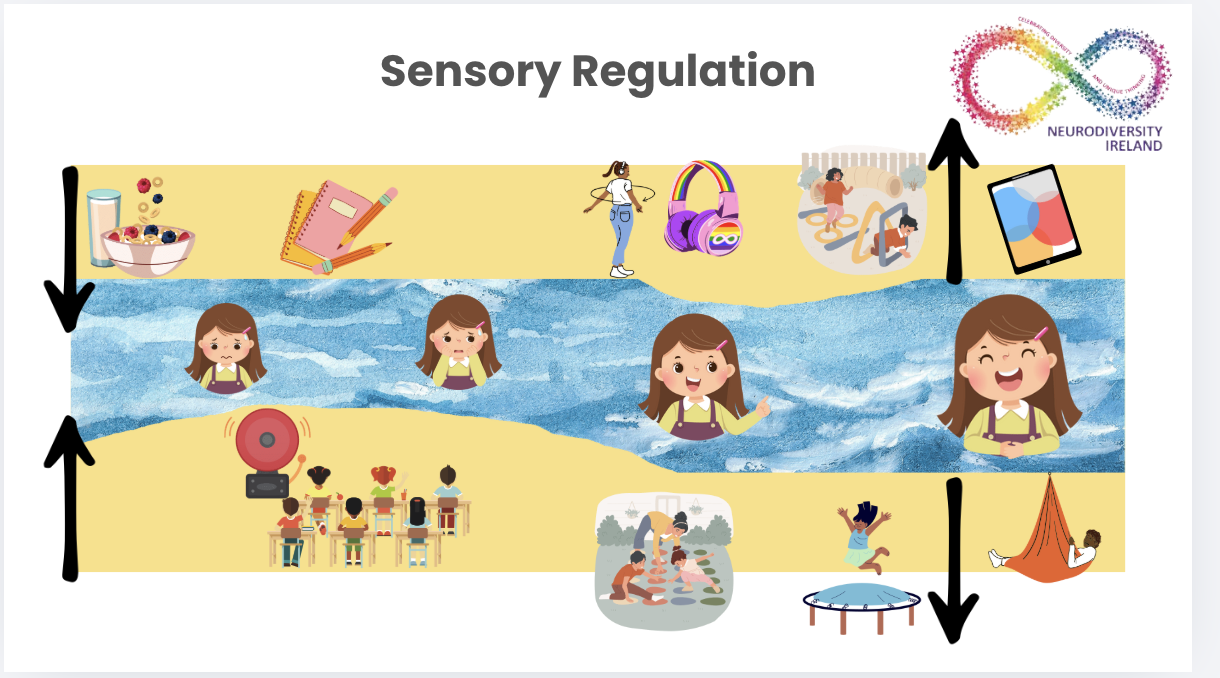

My Window of Capacity

I understand the window of capacity as something that opens and closes depending on nervous system load.

Imagine capacity as a window. The curtains are the demands, pressure, and stress building up on the nervous system.

As pressure increases, the curtains begin to close. When they are partly closed, access becomes reduced. When they are fully closed, the nervous system is in survival mode and many everyday activities are no longer accessible.

This is not about motivation, willingness, or skill.

It is about nervous system capacity.

-

The curtains can close due to many interacting factors, including:

explicit demands and expectations

hidden or indirect pressure

sensory overload or sensory mismatch

loss of autonomy or consent

unpredictability and lack of safety

cumulative dysregulation over time

Often it is not one demand, but the build-up of many small pressures that closes the window.

-

Each person has a unique window of capacity.

To understand an individual’s window, we need to understand:

their neurotype and overlapping neurodivergence

their history of stress, trauma, masking, or burnout

sensory interests, sensory sensitivities, and sensory safety needs

executive functioning and cognitive load

communication differences

physical health, sleep, and interoceptive awareness

Two people can experience the same environment very differently. What is manageable for one nervous system may be overwhelming for another.

-

The goal is not to force the window open.

Capacity reopens when pressure is reduced and safety is restored.

This includes:

reducing unnecessary demands

honouring autonomy and consent

increasing predictability

supporting regulation through relationship and environment

maintaining unconditional positive regard

When the curtains open, access returns , often gradually and unevenly.

© 2026 Sorcha Rice.

All content on this website, including written material, frameworks, and resources, is protected by copyright.

Educational and non-commercial sharing is permitted with attribution.

Commercial use, reproduction, or adaptation requires written permission.

Fluctuating Capacity

Our window of capacity is never static.

For all humans, capacity naturally opens and closes across the day, across environments, and across life stages. Fatigue, illness, sensory load, emotional stress, excitement, and change all influence nervous system capacity.

The goal is not to keep the window permanently open.

That is neither realistic nor healthy.

What matters is:

recognising when the window is beginning to close

understanding why it is closing

knowing how to reduce pressure and restore safety

Recognising a closing window

A window often begins to close before crisis.

Early signs may include:

increased dysregulation or withdrawal

reduced communication or increased scripting

changes in feeding, sleep, or toileting

increased need for autonomy or certainty

reduced capacity for sensory input or demands

These are not problems to correct. They are early nervous system signals.

Understanding PDA

In this free 20-minute webinar, I share a neuroaffirming overview of PDA, drawing on lived experience and occupational therapy perspectives. Ideal for parents, educators, and anyone wanting a more compassionate understanding.

Why this understanding matters

When we expect capacity to stay open at all times, we misinterpret natural nervous system fluctuation as failure.

When we understand fluctuation as normal, we can support regulation proactively rather than reactively.

The aim is not endurance, building resilience or tolerance.

The aim is safety, flexibility, and recovery.

Why Occupational Therapy is foundational for PDA support

Occupational therapy works at the level of the nervous system, not behaviour.

For PDA, OT focuses on:

sensory processing and sensory safety

interoception and internal state awareness

co-regulation rather than self-control

reducing unnecessary demands

increasing predictability in environments

supporting autonomy in daily occupations

This lens shifts the question from: “How do we change behaviour?” to: “What is this nervous system communicating, and how do we support it safely?”

Lived experience matters

I am autistic and ADHD, with lived experience of PDA, masking, and burnout.

That matters because:

PDA is often misinterpreted when viewed only through external behaviour

Masked distress is frequently missed in schools and services

Many PDAers are supported after burnout, not before (including myself)

My work sits at the intersection of clinical training and lived nervous system knowledge. One does not replace the other.

My Experience of School Burnout

As a teenager, I experienced significant school burnout and had to leave school for a time period. This was not due to a lack of ability or motivation, but to prolonged nervous system overload in environments that prioritised performance, compliance, and coping over safety and autonomy.

From the outside, I appeared to be managing. Internally, my capacity was closing. That experience shapes how I recognise masked distress, fluctuating capacity, and the long-term cost of pushing through environments that do not feel safe.

Why behaviour-based approaches don’t work

Many common approaches focus on:

increasing tolerance to demands

rewarding compliance

ignoring or extinguishing “undesired” behaviour

teaching emotional regulation as self-control

For PDA nervous systems, these approaches:

increase threat

reduce autonomy

escalate distress

deepen masking and burnout

When behaviour is treated as the problem, the nervous system is ignored.